Professional Trust – #APConnect by Dr Christina Donovan

A Question of Competence: professional trust as a condition for Advanced Practitioner effectiveness

Back in the heady days of the first lockdown, Lou Mycroft and I made a short video as part of #BrewEdFe’s #AmouseBouche series. In it, we outlined three key elements of trustworthiness (watch at your own risk…).

- Competence

- benevolence and

- integrity

(or C.B.I as we called it) are characteristics widely accepted in the field of trust research as being core to an individual’s assessment of trustworthiness in others. In other words, we want to know that the person we are choosing to trust is able to do what we are trusting them to do, that they have our best interests at heart, and that we find the principles (or values) that guide their conduct acceptable to us.

However, while perception might be a powerful indicator of trustworthiness, it doesn’t necessarily tell us much about our trustfulness, or whether we are willing to commit to the act of trusting in others based on this assessment (Möllering, 2019). Building and maintaining trust is a reciprocal and relational process, and as a shared endeavour it is something that we must work together at to maintain and reproduce. This is also something very easily overlooked in our day-to-day working life, and in the high-risk environments often endemic to FE landscape, making positive trust assessments of other colleagues becomes difficult and often becomes replaced by contracts (eg, I will trust you when/if you produce x/y). Particularly within organisational hierarchies, this approach can undermine professional autonomy and agency. This context is important when we think about the role of the Advanced Practitioner (AP), as the findings of our recent internal evaluation of the #APConnect Y3 programme suggest that the extent to which APs have the freedom to practice as affirmative change agents in their institutions is shaped powerfully by this organisational culture.

For these reasons, I want to spend some time here reflecting upon the first of these three elements of trustworthiness: competence, and its relationship to professional autonomy. This is because professional trust involves moving beyond simply perceiving competence, and requires us to act upon it through the delegation of authority. In the context of advanced practice, it means we must revisit not only conditions for trusting APs, but what it is we are trusting APs to do. Reviewing the competence of APs in this way is crucial to their effectiveness in practice.

The specificity of ‘competence’

The word ‘competence’ has a loaded definition, and carries different connotations across contexts. The Oxford English Dictionary lists no less than eight different definitions related to its use including: having the means to do something with comfort or ease, sufficiency of qualification or skill set, as well as legal capacity (or power) to undertake certain duties. Naturally in education, we tend to err towards the ‘qualification’ definition, and there is a specific set of skills associated with ‘qualified’ teacher status. These are clearly outlined in the current ETF Professional Standards and in this sense, we might agree that ‘competence’ in an educational context refers to an ability, or a set of skills that can be observed and verified.

However, in a seminal paper on the study of trustworthiness, Mayer et al. (1995) define ‘ability’ (often used interchangeably with ‘competence’) as “a group of skills, competencies and characteristics that enable a party to have influence in a specific domain”. The inclusion of influence in this definition represents a departure from a simple list of observable skills or attributes that we might expect an individual to have. Instead, it further suggests that competence/ability constitutes a power to, a capacity – even an authority – to alter or change something. In comparison, the definition of competence commonly used in the education sector seems impoverished. For me, this definition challenges the discourse of accountability that we see in the education sector, as if we are to be held accountable, we must also be competent. In the case of the AP, we might suggest that rather than work towards a set of often pre-determined outcomes, they should also have it within their competence to influence what those outcomes should look like.

The need for professional trust in advanced practice

In our evaluation of the #APConnect programme, notions of competence became a point of tension for the Advanced Practitioner, as they felt that their levels of agency were often constrained by the management structures they fell within. While, as Advanced Practitioners they may have been perceived as technically competent to perform their role (and this is indeed one of the privileges of the position they occupy), this did not always translate to their ability to influence or impact change where they felt it was needed, particularly in relation to quality improvement strategy. A clear difference emerged between the way APs understood their role, and the way they experienced it in practice. APs often found themselves unable instigate the changes they felt were important as these were at odds with a sometimes narrowly defined, outcomes-orientated understanding of the role at a leadership level. We found that APs’ professional judgement needs to be trusted to allow for greater agility and flexibility in their role, and notions of competence are centrally important to this.

Allowing APs greater autonomy involves those who lead APs not just perceiving them as trustworthy, they must also practice trust. Fundamental to understanding the nature of trust is that we cannot trust without taking a risk, and so trusting behaviour is linked to our willingness to assume that risk. In other words, trust cultivates a healthier attitude towards risk; important for creativity. The problem is that in many FE organisations; we are trying to design out risk by controlling the outcome. Put simply, to trust in the truest sense of the word, makes us vulnerable within a system built upon individual accountability. A shift towards a culture of professional trust would require us to build vulnerability back into organisational practice.

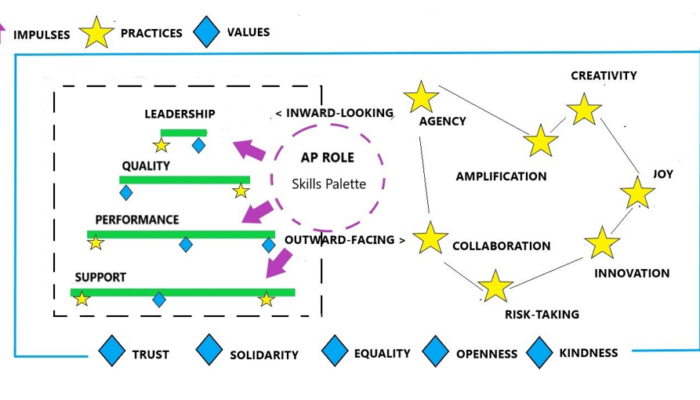

The ‘Christmas Tree Model’ APConnect Co-Evaluators 2021

Values, Practices, Impulses

Vulnerability lies at the heart of our ability to trust. It is vulnerability that opens opportunities up to innovation and creativity, and it is our decision to trust that allows us to take positive risks that facilitate this innovation. Management research has shown that the ‘vulnerable involvement’ of managers (or a willingness to expose their own gaps in knowledge with employees) allows them to build positive working relationships in which the tacit knowledge, skills and expertise of employees are valued (Shapira, 2019). This in turn has a relationship with improved quality, greater innovation and increased cooperation. Conversely, resistance to vulnerable involvement is linked to detached or more autocratic forms of leadership. In this sense, we might say that it is through enacting vulnerability, that we achieve transformation in practice (a culture which was beautifully illustrated by the Constellations of Practice). This is what Brené Brown would call rumbling with vulnerability: the ability to stay present in our vulnerability and to use it to work towards change. Lou Mycroft and Gary Husband (2019) remind us that no single individual is transformational; instead, we must understand transformation as arising from a set of conditions which allow for it to take place. Unfortunately, in the FE sector, these spaces are not always forthcoming. This lack of vulnerable involvement means that many contexts, competence does not always translate to the kind of autonomy described here because of other powerful interests at play; particularly in terms of what constitutes ‘quality’ in teaching and learning.

In the first comprehensive piece of work exploring the role of the Advanced Practitioner, the Institute for Employment Studies found that effective AP work took place in supportive organisational cultures (Tyler et al., 2017). In our evaluation, we found that more attention needs to be paid to how this culture is produced. We found that APs felt at their most effective when they were rooted to a particular set of values (trust, solidarity, equality, openness and kindness). These values allowed them to build relationships across and between college contexts, and promote collaborative practices that created space for innovation, creativity, and knowledge exchange. It was the embodiment of these values that led to the impulse (Zahariea, in Donovan and Forrest, forthcoming) to effect change within their organisations. To allow for these impulses, however, we must assume professional autonomy as a prerequisite. The very idea of acting upon ‘impulse’ is anathema to the ways in which many colleges work, but this is exactly what Thedham (2019) advocates in his guide for leading APs, saying that to foster AP effectiveness, managers must “give APs the freedom to act”. This involves developing a culture of trust, where the professional autonomy of APs is valued and respected. This requires us to view trusting as a practice, and thus renew our understanding of competence. This would allow the space necessary for APs to enact their impulse to create change.

References

Donovan, C. and Forrest, C. (Forthcoming) Re-thinking the role of the Advanced Practitioner: AP Connect Y3 Evaluation Strand Final Report. Education & Training Foundation

Mayer, R., Davis, J. and Schoorman, D. 1995. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. The Academy of Management Review. 20 (3) pp. 709-734

Möllering, G. 2019. Putting the spotlight on the trustor in trust research. Journal of Trust Research. 9 (2) pp. 131-135

Mycroft, L. and Husband, G. 2019. The cost of everything and the value of nothing: What is next for the FE sector? In: Tummons, J (ed.). PCET: Learning and Teaching in the Post Compulsory Sector. London: SAGE

Shapira, R. 2019. ‘Jumper’ managers’ vulnerable involvement/avoidance and trust/distrust spirals. Journal of Trust Research. 9 (2) pp. 226-246

Thedham, J. 2019. How managers can support and develop Advanced Practitioners – an organisational approach. Education & Training Foundation. Available online: https://www.et-foundation.co.uk/supporting/professional-development/practitioner-led-development-and-research/advanced-practitioners/resources/

Tyler, E., Marvell, R., Green, M., Martin, A., Williams, J., Huxley, C. 2017. Understanding the role of Advanced Practitioners in English Further Education. Education & Training Foundation. Available online: https://repository.excellencegateway.org.uk/Advanced_Practitioners_Executive_Summary_-_Final.pdf